What Does Milei’s Economic Record Truly Show? A Response to Critics & An Explanation of the Recent Fall-Out

This article was made by the Classical Liberal Charles Lajoie. See more of him on Twitter @lemechantneolib or on Substack at UnPeron — Unlearn Peronism!

During the last 3 months, much ink has been spilled on Javier Milei and Argentina. A peso run, a Washington “bailout” (actually a currency swap from which the US made a significant profit), and an unexpectedly favorable showing for La Libertad Avanza in the late-October midterms have drawn commentary from a wide variety of individuals. While the man’s record is far from perfect, the anti-Milei side of the economic debate has often shown itself to be disingenuous. It has tried to paint the Argentine president as the architect of the country’s recent economic troubles, despite—as we will see—all the evidence to the contrary. Kinsee Crowley and Kim Hjelmgaard for USA Today, a supposedly neutral and middle-of-the-road news outlet, stated that his economic agenda “has led to a volatile peso currency and seen investors aggressively dump Argentine stocks and bonds.” For journalists Heather Stewart and Aditya Chakrabortty at The Guardian, it’s proof of populists crashing the economy and Mileinomics ruining the country.

Unfortunately, these are not even the worst articles to be written for The Guardian on this subject. This dishonorable title has to go to Tiago Rogero and Facundo Iglesia’s ‘You’re either poor or rich’: the Argentinians struggling under Milei’s chainsaw austerity. As one can gather from its headline, the authors first argue that Javier Milei’s administration increased income inequality. Yet, there has been a slight reduction in inequality since Milei took office, as the Gini coefficient went from 0.435 in 2023’s fourth trimester to 0.424 in 2025’s second trimester.

Then, they argue that “wages and purchasing power have nosedived.” In actuality, real wages (total) have been constantly increasing since January of 2024. Like for almost every other economic indicator, there was an initial degradation—which began before Milei but was worsened by a necessary devaluation in Milei’s first month in office—directly followed by rapid improvement. It’s true that public sector wages haven’t or have barely reached pre-Milei levels, and that those in the formal or registered private sector have been stagnating since January of 2025. However, overall levels are still rising as gains overwhelmingly come from the informal or non-registered private sector of the economy.

Weirdly enough, the authors tie the supposed wage losses and increase in inequality to the state of this informal private sector, writing that “informal workers now account for 43.2% of the labour force and that half of them don’t earn enough to get by.” They are not “subject to labour laws” like their counterparts in the formal sector, they note. The real wages informal workers earn are represented by the blue line below, formal workers by the green line. As you can see, informal workers’ wages have been surging under Milei after collapsing under Fernandez (2019-2023), and this group now has the highest earnings of all. While it’s still possible that half of them “don’t earn enough to get by,” I don’t know which standards were used to make the claim, and poverty is significant among all Argentines. Informal workers are also said to be disproportionately young, and young people have remained the strongest supporters of the president.

Yanis Varoufakis, a far-left Greek economist, has given his two cents on the situation too. While we vehemently disagree on pretty much everything, I nonetheless appreciated his prudence in attributing economic problems to political ideologies he has little sympathy for, in this case libertarianism. Unfortunately, his article remains filled with factual inaccuracies. He begins by dismissing the reduction in the poverty rate as “a mirage.” “The only reason the relative poverty index dropped,” he argues, “was that median incomes had fallen faster than those at the bottom.” This is complete nonsense. The poverty rate calculated by the INDEC, the most authoritative source on economic data in Argentina, is a measure of absolute—not relative—poverty. Hence, the absolute poverty rate dropped from approximately 49.5% the month Milei was sworn in (UCA)—or, more charitably to Milei’s predecessors, 41.7% when calculated as an average of the whole second semester of 2023 (INDEC)—to 31.6% as of the first semester of 2025 (INDEC). This is the lowest it’s been since 2018.

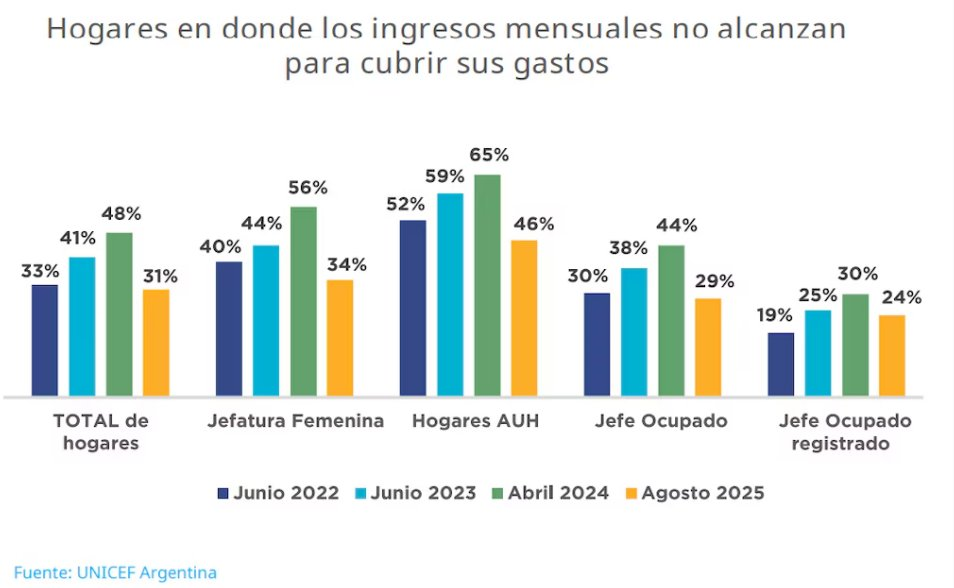

According to the UNICEF’s 9th Rapid Survey—hardly a right-wing organization—the number of households with children and adolescents with a monthly income insufficient to cover living expenses went from 41% in June of 2023 to 31% in August of 2025, and although of varying degrees, the reduction applies alike to female-headed households, households subject to the country’s non-contributory child allowance program (AUH), households headed by an employed person, and households headed by an employed person in the registered (or formal) sector of the economy.

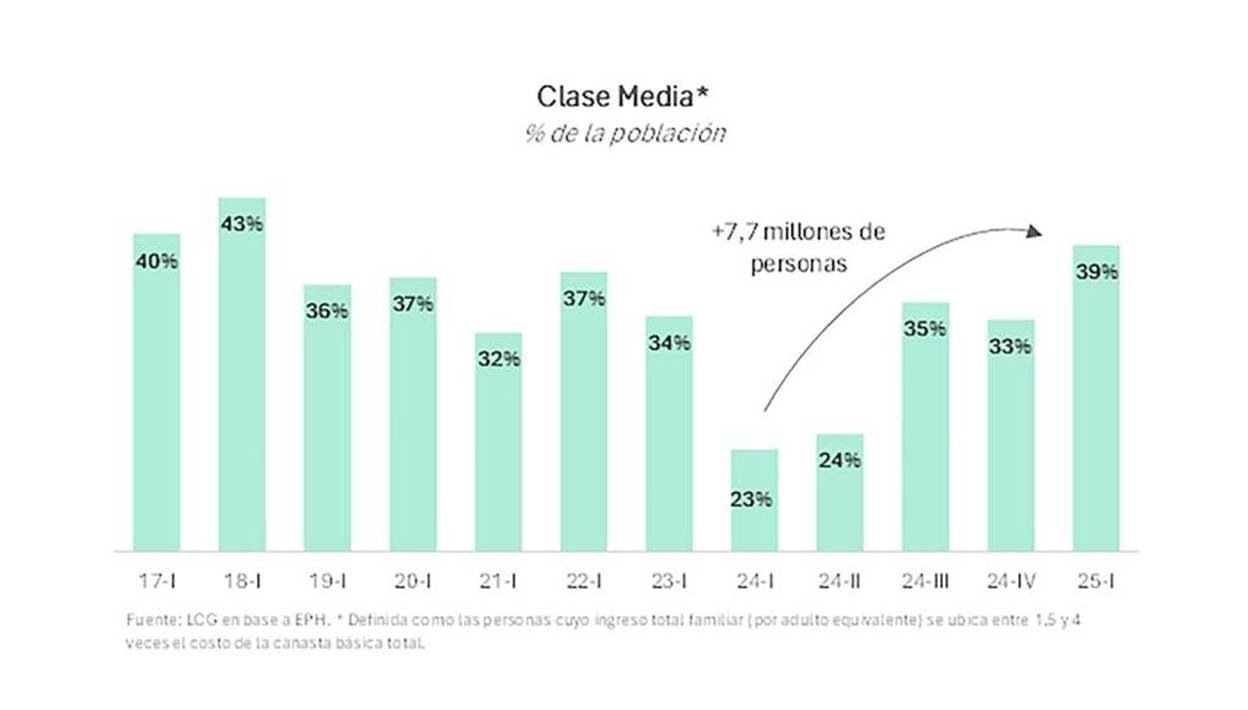

Additionally, the middle class—defined as people earning between 1.5 and 4 times the cost of the total basic consumption basket—reached similar levels to pre-pandemic Argentina in 2025’s first quarter. There was an increase of 7.7 million people or 15 percentage points in a single year under the Milei administration.

In drawing a list of Milei’s corrupt predecessors, Varoufakis makes “surprising” omissions. For example, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner—arguably the most notoriously corrupt Argentine president of the 21st century, who has been convicted to 6 years of jail time—doesn’t make the cut. She was, of course, a progressive Peronist (or Kirchnerist). Instead, Varoufakis mentions the moderate market-liberal Mauricio Macri, a man who never faced any corruption charge (only allegations) and who is linked to anti-corruption efforts.

Varoufakis then accuses Milei of not liberalizing the “money market” and borrowing “zillions of dollars.” Here, Philipp Bagus offers a strong correction for the Mises Institute:

“In reality, Milei did not borrow “zillions of dollars”; he actually reduced public debt. His government achieved a budget surplus as early as January 2024, just one month after taking office, and has maintained it ever since. Rather than adding new net public debt, the administration has merely refinanced obligations inherited from previous governments. In fact, under Milei the national public debt was reduced by approximately USD 40 billion, and the debt-to-GDP ratio fell dramatically—from 154.6 percent in 2023 to 84.65 percent in 2024. As for the exchange-rate regime, it is moving in the right direction—toward greater monetary freedom. Capital controls and the cepo cambiario have been largely dismantled, allowing for an increasingly liberalized foreign-exchange market.”

Varoufakis follows by painting Milei as Menem 2.0, predicting the same tragic fate Argentina faced after the latter’s time in office. Since Carlos Menem has received praise from Javier Milei on multiple occasions, and members of the Menem family now occupy key positions in his government, this comparison is not completely uncalled for. In his first administration, Menem had achieved tremendous economic success by adopting market reforms aligned with the “neoliberal” Washington Consensus of the time (except on unemployment). During the second Menem administration, however, public deficits grew at alarming rates and eventually became completely unsustainable.

This was both a consequence of provincial governments’ spendthrift policies and late-Menem’s own unwillingness to curb spending. Indeed, in the 1998 budget, his administration proposed to increase it—while enacting tax cuts—despite rising deficits. This, in combination with the rigidity of the Convertibility Plan’s fixed exchange rate, caused a recession in 1998 and would eventually lead to the disaster of 2001. Could Javier Milei’s government go down the same path? Of course, but Milei has thus far shown greater credibility on fiscal matters. As Bagus mentioned, he has run constant primary surpluses since he was elected, and La Libertad Avanza securing a third of Congress during the midterms—and therefore its veto power—means that Milei will have sufficient legislative support to protect the budget surplus if he’s willing to do it. Ideological coherence, as a libertarian economist rather than an unorthodox Peronist, also works in Milei’s favor.

So, what truly happened in the last few months?

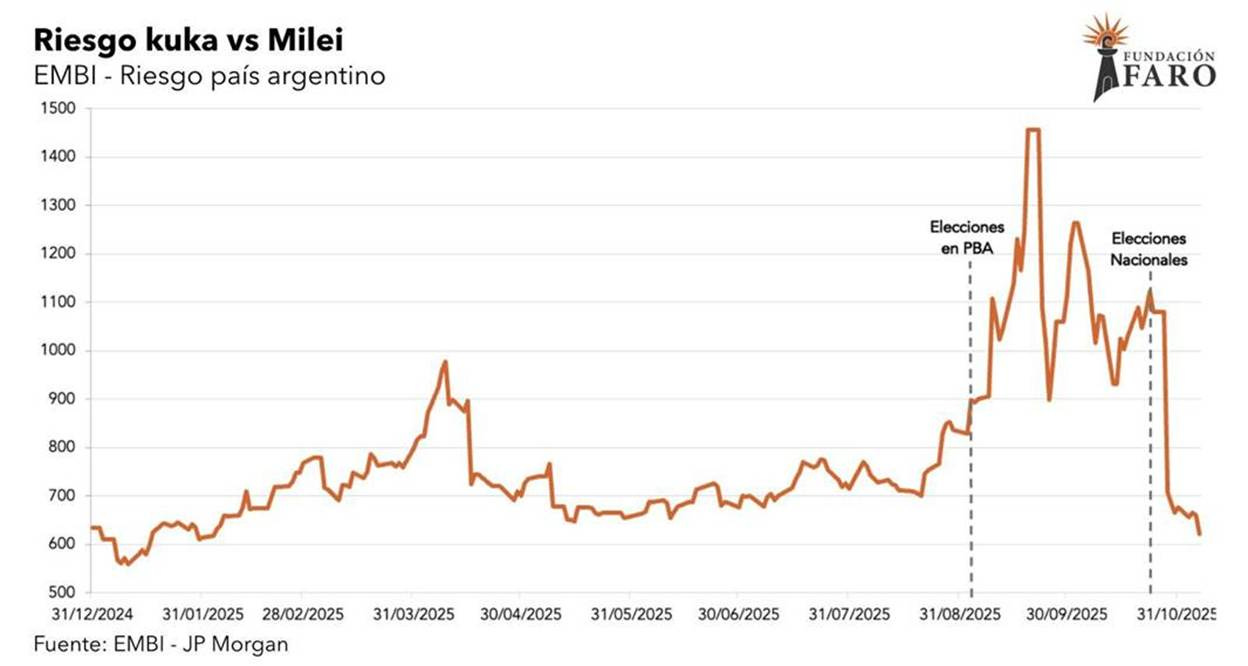

The market reaction to the midterm results has provided strong vindication of the “Kuka Risk” explanation of the peso run and subsequent economic troubles. That is, the idea that investors fearing the economic impact “kukas” (Kirchnerists, i.e. left-wing Peronists) would have if they won enough seats to block Milei’s reform agenda in the October midterms. It’s uncontroversial to say that what triggered the crisis were the September 7th elections in the province of Buenos Aires—in which Kirchnerists won by a substantial lead that pollsters had failed to predict—even though most commentators didn’t or only briefly acknowledged this.

Country risk, a measure of the probability of an economy to default on its sovereign debt, had risen to more than 1,100 basic points on September 8th, 202 points above the previous measure (3 days earlier) and the only time the 1,000-pts threshold had been crossed in 2025. However, it wouldn’t be accurate to say September 7th marked the very beginning of the trend. The real departure occurred on August 19th, when the Karina Milei scandal began making the news. This, of course, hurt Milei’s popularity and reduced his odds of winning in October. Hence, from that date until September 5th, a period of a little more than 2 weeks, country risk had already increased by 206 points.

What was country risk before the Karina Milei scandal erupted, and what is it today, 2 weeks after the midterms?

700 then, and 614 now (November 17th). In comparison, country risk stood at 2,412 two days prior to Milei’s 2023 election. Between October 24th—the last datapoint before the midterms—and October 27th alone, country risk fell by a staggering 373 basic points. In a period of two weeks, it dropped by an additional 109 points, as markets rallied and hit their highest point in Argentina’s history (just like they had tanked after September 7th). So, Kuka Risk is gone, at least for now. This, of course, doesn’t mean that default risk has been overcome in Argentina; a country risk of 614 basic points is still high. Latin America, which is not exactly a model continent for sane economic policy, had an average of 366 bps in August (excluding Venezuela, at over 10,000 bps).

And the peso run?

As a result of restored investor confidence, there has been a large and unexpected influx of US dollars in the Argentine markets during the last 3 weeks, and both the official and the blue dollar exchange rates have stabilized at around 1,430 pesos. Growth forecasts for 2026 have recovered as well, as interest rates fell sharply (a reduction of approximately 75% for short-term rates). For Daniel Artana, chief economist at the Foundation for Economic Research on Latin America, “the worst is over, and there is good news ahead” (translation is mine). The currency crisis is referred to in the past tense, even though Artana believes its consequences will continue to be felt by Argentines for some time.

In this context, Milei’s approval rating has rapidly recovered. The latest numbers come from Morning Consult and were obtained between November 6th and 12th. They show a 56% approval rating for the Argentine president, and a net approval score of +16. Claudia Sheinbaum, the left-wing Mexican president whose popularity was repeatedly highlighted in the last year, trailed far behind at 41% (-11). From October 29th to November 2nd, Giaccobe Consultores measured Milei’s positive image at merely 42.4% (-10), while Opina Argentina measured it at 48% (-4) between November 1st and 4th and, as previously mentioned, Morning Consult estimated it at 56% (+16) between November 6th and 12th. The samples for the 3 polls were of approximately 2,000 individuals each.

While the Morning Consult poll is somewhat a positive outlier for Milei among the few post-election ones we have, the polling agency’s center-left orientation doesn’t fit the notion of artificially inflated numbers and its moving average methodology is meant to capture real- time changes more accurately. This last point is crucial considering that great news about the state of the economy are most likely driving the improvement in Milei’s approval, and some have transpired or have been reported gradually since the midterms. But, even if we stick to the Opina Argentina study conducted in the first days of November, Javier Milei’s government—rather than Milei himself—holds a positive net approval rating (+2), his personal image is back to its March 2025 levels, and the latter rating ranks highest among all Argentine politicians. Indeed, the libertarian leader is directly followed by his Minister of National Security Patricia Bullrich with 47%, the center-right former president and ambivalent Milei ally Mauricio Macri with 45%, and his Minister of Economy Luis Caputo with 42%. Peronists trail behind. Furthermore, Milei’s government is viewed positively by 63% of young people.

Granted, Javier Milei’s presidency hasn’t exactly been free of economic setbacks either. Thus far, Argentina’s economy hasn’t grown nearly as much as most predicted for 2025, and an unexpected hike in unemployment at the beginning of the year has revealed lasting vulnerabilities in its labor market. For some groups, the initial impact of the 2023 devaluation has not been fully reversed, and many experts now argue another one may be inevitable (Milei disagrees). If they are correct, Javier Milei’s approval could fall dramatically. The recent months have shown that Argentina’s economy is still extremely fragile and, therefore, unadulterated optimism and calls of an economic miracle should probably be tempered for now. Still, the libertarian president has already done much better than his predecessors, especially considering the mess he inherited, and despite the popular lies and distortions suggesting otherwise in the mainstream media.